Henri Matisse in Beauvezer, 1935

© Picture: Henri Matisse Archives. (c) D.R.

Early 1900s

In 1898, two journeys would prove to be be fundamental for the subsequent course of his artistic path: one to London where he reveled in the works of William Turner, then another to Toulouse and Corsica where he discovered the light of southern France. After returning to the North for a short period, it is at the beginning of the following century that his art reached a critical turning point. His use of watercolor in painting from nature and his meeting with Paul Signac in 1904 allowed him to free himself from the traditional use of color, leading to the invention of Fauvism during the summer of 1905 spent in Collioure with André Derain. In 1906, he bought his first African mask and introduced Picasso to this art. That same year, he visits Algeria where the experience of the desert overwhelms him and gives him "une envie de peindre à tout déchirer". ("an irrepressible urge to paint") 4.

Driven by both his color inventions and recent inspiration, he embarked upon an intense creative period with the commission of two decorative panels for the Russian collector Chtchoukine - La Danse and La Musique - around 1909-1910. The masterful series of symphonic interiors, notably L'Intérieur aux aubergines of 1911, was the high point of this decade during which he also discovered Muslim art and Spain. Quick to continue his openness to the world, the sojourns in Morocco in 1912 and 1913 cemented his irresistible attraction for the East.

In the course of his travels, Matisse built up a collection of objects, furniture and fabrics that he included in his works: "The object is an actor: a good actor can act in ten different plays, an object can play a different role, in ten different paintings.."" 5 his diversity of sources, enriched over time by his travels, nourished his artistic reflection and the iconography of his works. In approaching the notions of decoration, Matisse moved away from exactitude – which according to him was not the truth - and sought the synthesis of form in the essence of its emotions. In 1916, Matisse produced two major large-scale works: Les Marocains and Femmes à la Rivière and spent the war years living between Issy-Les-Moulineaux and Paris.

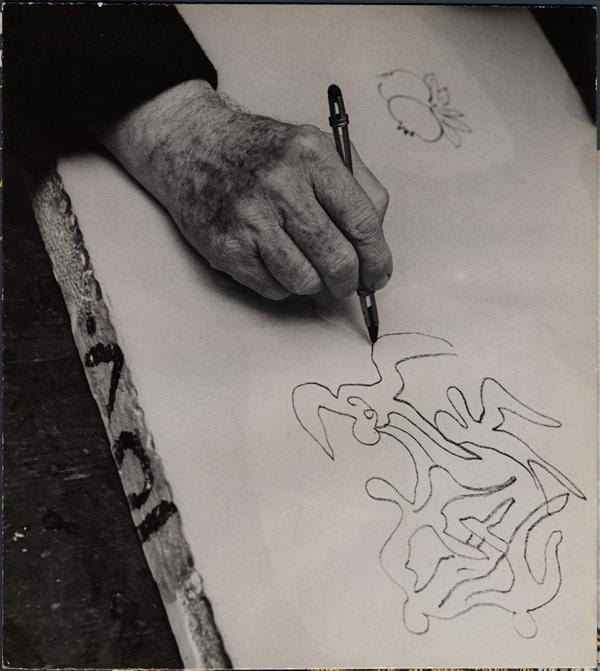

Henri Matisse at work, 1947, by Ina Bandy

© Picture: Henri Matisse Archives. (c) D.R.

The 20’s

The results of his explorations were dizzying, pushing him to depart for Nice at the end of October 1917, where he settled definitively at the beginning of the 1920s. In leaving his studio of Issy-les-Moulineaux for Nice he was able to create a universe dedicated to what became his obsession for ten years: the Odalisques, where the models lent themselves to his game of accessorization. Matisse recalled the flamboyant fabrics from his native region to create interiors with an abundance of materials and patterns. Intoxicated by the infinite variations of the subject, he multiplied these scenes of interiors; painting, drawing and sculpting young women naked or dressing them with clothes brought back from Morocco. In 1920, he created the sets and costumes for Diaghilev’s ballet Le Chant du rossignol, his first decorative experience outside the flat surface of painting.

Henri Matisse in Beauvezer, 1935

© Picture: Henri Matisse Archives. (c) D.R.

The 30’s

In 1930, ever more demanding of himself and eager to renew his art once again, he left for Tahiti to discover another place and another light. At first, it was not the destination itself that moved him, but the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by boat from Le Havre to New York, as well as the crossing of the United States by car and train, from East to West in order to reach San Francisco and embark from there for Tahiti. 6 CThis journey radically transformed his perception of space and made him aware of a completely different scale, of the possibility of another vision. "Vast, so vast, if I were thirty years old, this is where I would come to work." 7 He was completely fascinated by the city of New York, as a confirmation of his new linear explorations undertaken shortly before his departure. "If I wasn't in the habit of seeing my decisions through, I wouldn't go any farther than New York, that is how much I find it to be a new world: it is as big and majestic as the sea - and on top of that one feels humanity." 8

After the eight-day boat trip, Matisse discovered Tahiti, gathering here the memories and sensations that would reappear clearly in his art about ten years later. There he swam in the lagoons and discovered the fauna and flora, enthralled by the colors and shapes that nature offered within his reach. On his return, during the 1930s, he alternated between decorative commissions and book design. The composition La Danse for Dr. Barnes in Merion (USA) and the illustration of Mallarmé's Poésies testify to his daring treatment of space and his propensity to move towards an ever-greater graphic and formal simplicity. After the delivery of the panels of La Danse to Barnes, his meeting Lydia Delectorskaya in 1934 allowed Matisse to reconnect with easel painting. From 1935, it was Lydia who embodied “la femme” in all her splendor, transforming herself for Matisse’s every inspiration, and she remained his preferred model until 1939. Major works were created (Le Rêve, Le Nu rose). His immediate surroundings served to support his imagination and the studio became the focus of his attention. Matisse was able to take a universal look at the world by showing the immediacy of his daily life.

Panels of the ceramic "La Gerbe", at Robert Rosolen's home, Villa Terron, Nice.

© Picture: Henri Matisse Archives. (c) D.R.

Early 40’s

In January 1941, Matisse underwent a serious operation in Lyon. The same year, in May, he returned to Nice and devoted himself mainly to drawing. Upheld by his unfailing optimism, he considered that he had been given a new lease on life. 9 He experimented with new techniques and committed to new book illustration projects. He produced many portraits where the extreme simplicity of the lines suggests both the outline and the modeling: " line is enough to evoke a face, there is no need to impose eyes or a mouth on people.... we must give the spectator free rein for his own reverie." 10

In 1943, he was persuaded by Tériade to create the book Jazz. Thanks to Jazz, Matisse gave true autonomy to the technique of gouache and cut paper. Although Matisse was somewhat disappointed by the printed result, he had the youthful feeling of having achieved a joyous balance between line, color and volume: "Cutting into raw color reminds me of the direct carving of the sculptor. This book was designed in this spirit. » 11 A sensation that was all the more enjoyable because Matisse had combined techniques and different means of expression - drawing, painting and sculpture - throughout his life, regularly exhibiting his sculpture alongside his drawings and paintings and representing his own sculpted works in his paintings. 12

Late 40’s

He also alternated scale, going from a sheet of paper to the monumental which he accomplishes in 1946 with the panels Océanie Le Ciel – Océanie La mer created on the walls of his Parisian apartment and based on his memories of Tahiti: "The things we consciously acquire allow us to express ourselves unconsciously with a certain richness. On the other hand, the unconscious enrichment of the artist is made of everything he sees and which he translates pictorially without thinking about it. An acacia tree from Vesubia, its movement, its slender grace, might have led me to conceive the body of a woman who dances". 13 This desire to create another space led him in the years 1946 to 1951 to the project for the Chapelle de Vence, where he was at once architect, artist and designer. The more Matisse felt trapped in his body weakened by age, the more he found the means to free himself from it through imagination. His immense wall compositions of paper cut-outs of the last few years testify to this capacity for renewal that he had cultivated throughout his life.

Until his death in 1954, his qualities of audacity, optimism and high standards led him to always think like a man of his time, open to the world and looking towards the future: "This technique of paper cut-outs literally carries me to a very great passion for painting, because by renewing myself entirely, I believe I have found there one of the main points of aspiration and artistic obsession of our time. By creating these cut and colored papers, it seems to me that I am happily going to meet the future. Never, I believe, have I had as much equilibrium as when I made these cut out papers. But I know that it is much later that we will realize how much of what I do today was in step with the future." 14

4 Letter to Henri Manguin, undated (June 1906), cited in Rémi Labrusse, "Matisse, Byzantium et la notion d'Orient", doctoral thesis, Paris, Université Paris 1, 1996, page 428; cited in Anne Théry, op. cit. page 278

5 EPA, op. cit. page 247

6 For a precise study of this journey see Jack Flam, Histoire et métamorphoses d'un projet, in cat. exp. Around a masterpiece by Matisse, the three versions of the Barnes dance, 1993-1994. Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

7 Letter of 10 March 1930 quoted by Pierre Schneider, Matisse, Paris, Flammarion, 1994, page 607.

8 Pierre Schneider, op. cit. page 606.

9 EPA, op. cit. Page 277 : Henri Matisse wrote to Marquet in 1942: "it seems to me that he is in a second life".

10 Henri Matisse's words to Paule Martin about the panels of the Chapel of Vence, reported in "Il moi maestro Henri Matisse", La Biennale di Venezia, n°26, December 1955. EPA, op.cit. p.274.

11 EPA, page 237

12 See Ellen McBreen's article on sculpture in Tout Matisse, edited by Claudine Grammont, published by Robert Laffont, Bouquins collection, 2018.

13 EPA page 126

14 EPA page 251